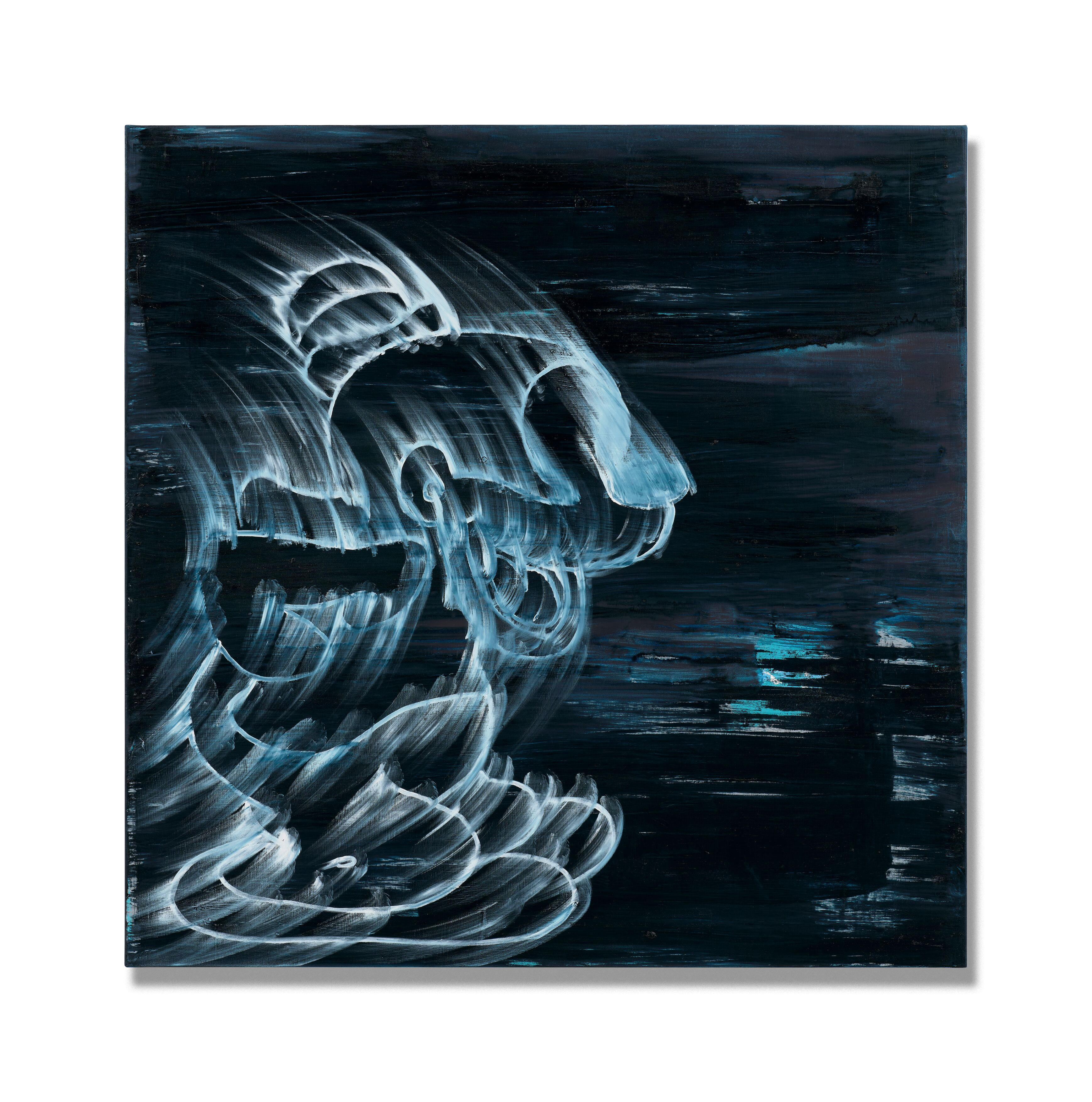

Gary Simmons

Hands on Hips

‘We are all haunted by the past and longing. A ghost is a presence you feel but cannot see. It’s the hidden element in the room, the mental traces that are always with us: personal experiences, fantasies, perceptions or world events. My work, in general, comes from the memories of events and images that I, and I imagine others, are haunted by.’—Gary Simmons

For over 30 years, Gary Simmons has probed film, architecture and American popular culture to create works that explore personal and collective experiences of race and class. Early in his practice, Simmons established a studio in a former school in New York City. There he encountered schoolroom objects, which became the material for artworks that addressed racial inequality and institutional racism through the filter of childhood experience. Simmons’ use of pedagogical materials, in particular readymade chalkboards, led to the formal and aesthetic breakthrough that would inform much of his subsequent work, in which the erasure of the image has been a powerful and recurring theme.

In his most recent paintings, Simmons returns to racist cartoon characters once prevalent in American visual culture; these first appeared in the artist’s seminal chalkboard drawings in the early 1990s. Introduced to audiences in 1929, Bosko and Honey were the first cartoon characters in the Looney Tunes franchise. Directly related to minstrel shows and based on degrading stereotypes of Black Americans, the characters were featured in more than 20 musical short films as singing, dancing simpletons. Portrayed as perpetually happy and innocent amid their serial misadventures, Bosko and Honey enact a world in which violence becomes a form of pleasure, and everything always turns out alright.

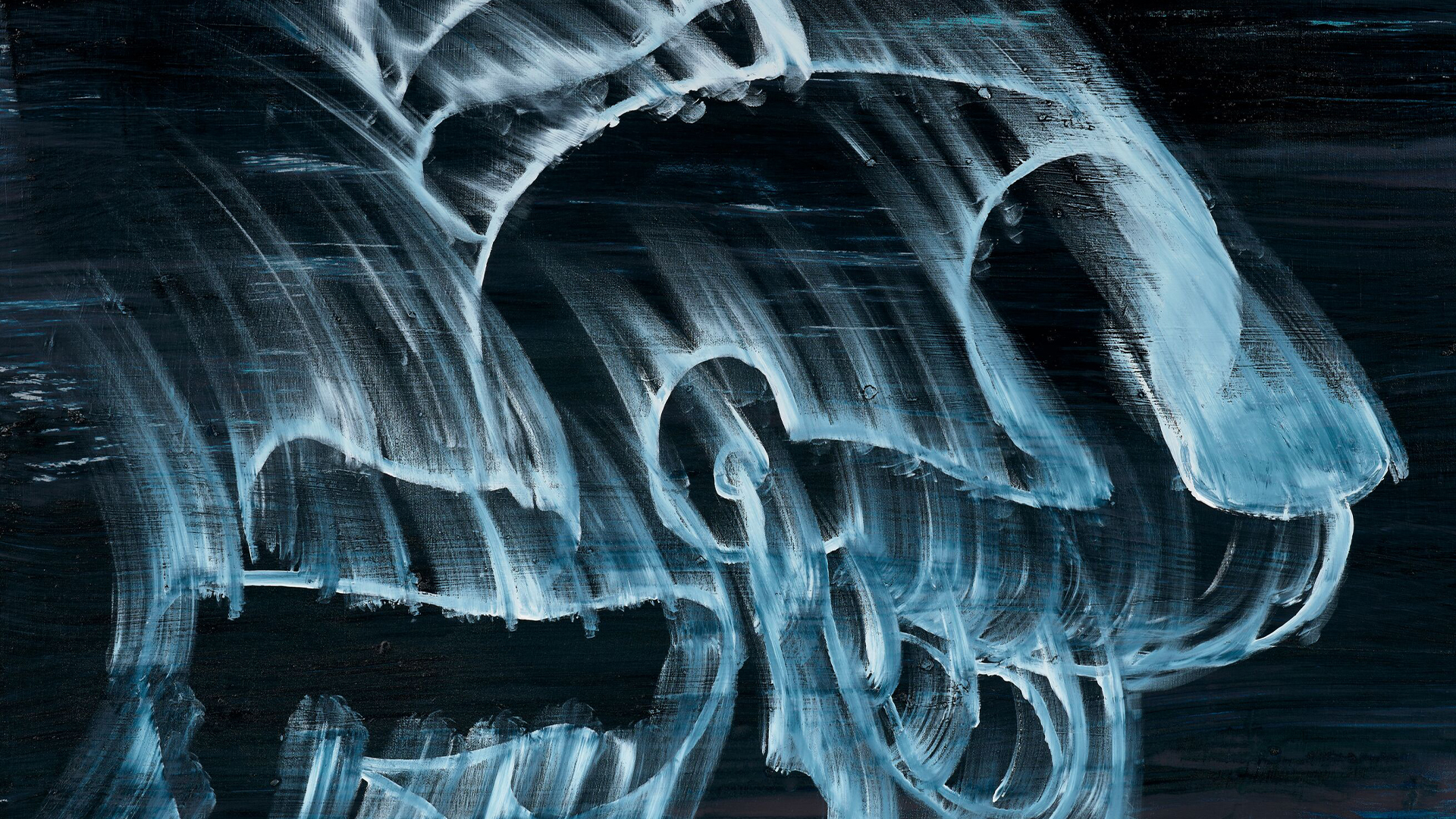

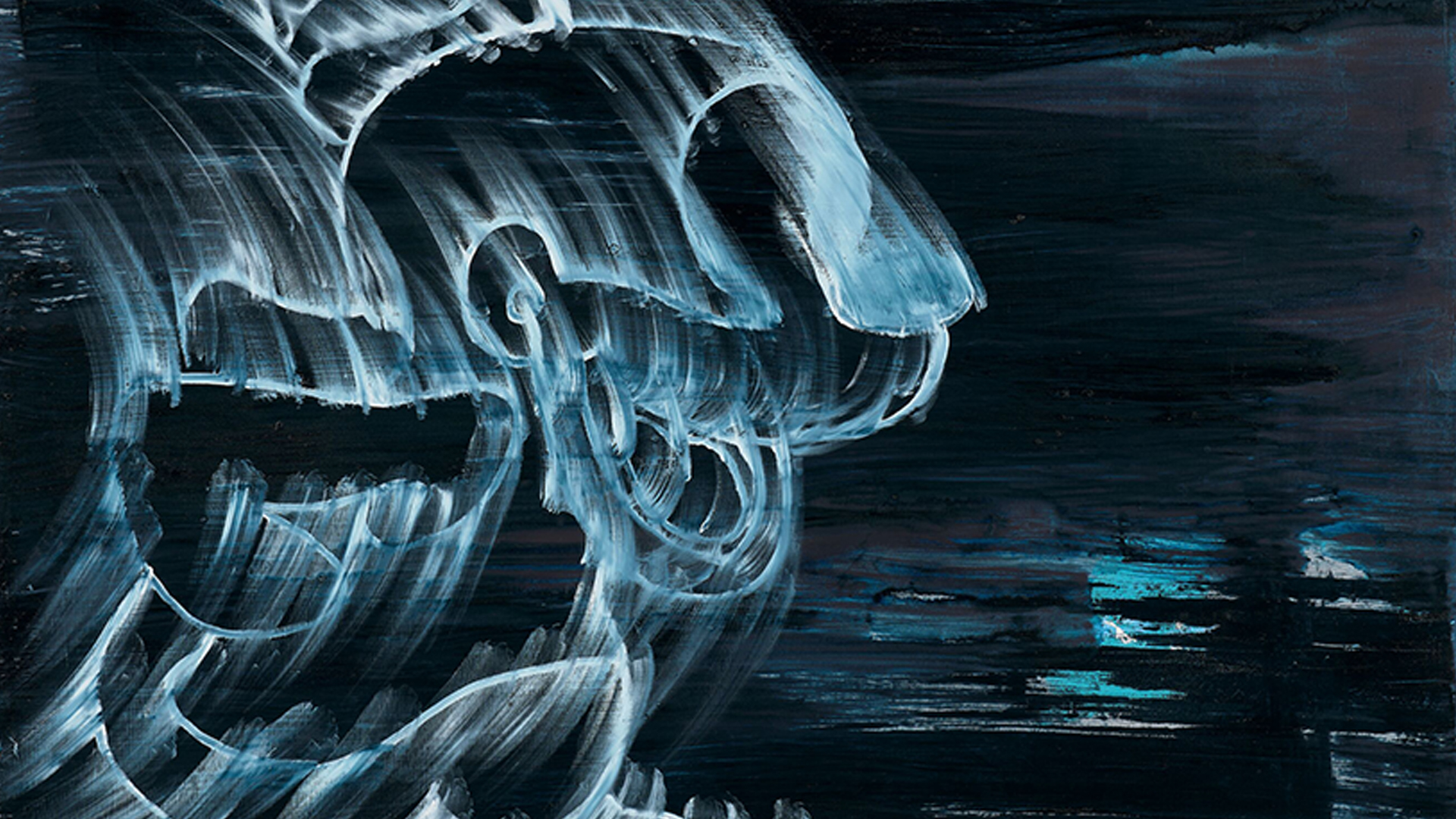

Intentionally erased from public view in recent years, Bosko and Honey—and the impulses and prejudices revealed by their enormous popularity—nevertheless remain alive in the soul of America. Simmons depicts Bosko on the surface of ‘Hands on Hips’ (2023) as a ghostly fragment. Isolating the faint specter as if it is a film still on canvas, Simmons draws attention to the fundamental disconnect between the topical sweetness of the image and the inherent violence of the racial stereotypes Bosko embodies. The work enacts a sense of nostalgia for innocent childhood entertainment, raising uncomfortable questions about the past while insisting on its unresolved status.

Simmons’ use of erasure is loaded with deep cultural significance. To create ‘Hands on Hips,’ the artist built up the canvas with layers of oil, wiping the surface while the paint was still wet in order to smear the image so that it emerges and disappears simultaneously. Commenting on the conceptual underpinning of his process, Simmons noted: ‘We can attempt to erase the stereotype, but the image won’t easily go away, it persists.’ [1] As critic Jan Avgikos noted in reference to the artist’s recent work, ‘Simmons’ new paintings roar with vengeance at the frightening, widespread resurgence of white supremacy, which is all too alive and well.’ [2] Retaining the lasting gestural marks of Simmons’ unique process, ‘Hands on Hips’ hints at the ghostly traces of the past and the transience of memory.

About the artist

Gary Simmons uses icons and stereotypes of American popular culture to create works that address personal and collective experiences of race and class.

Gary Simmons uses icons and stereotypes of American popular culture to create works that address personal and collective experiences of race and class.