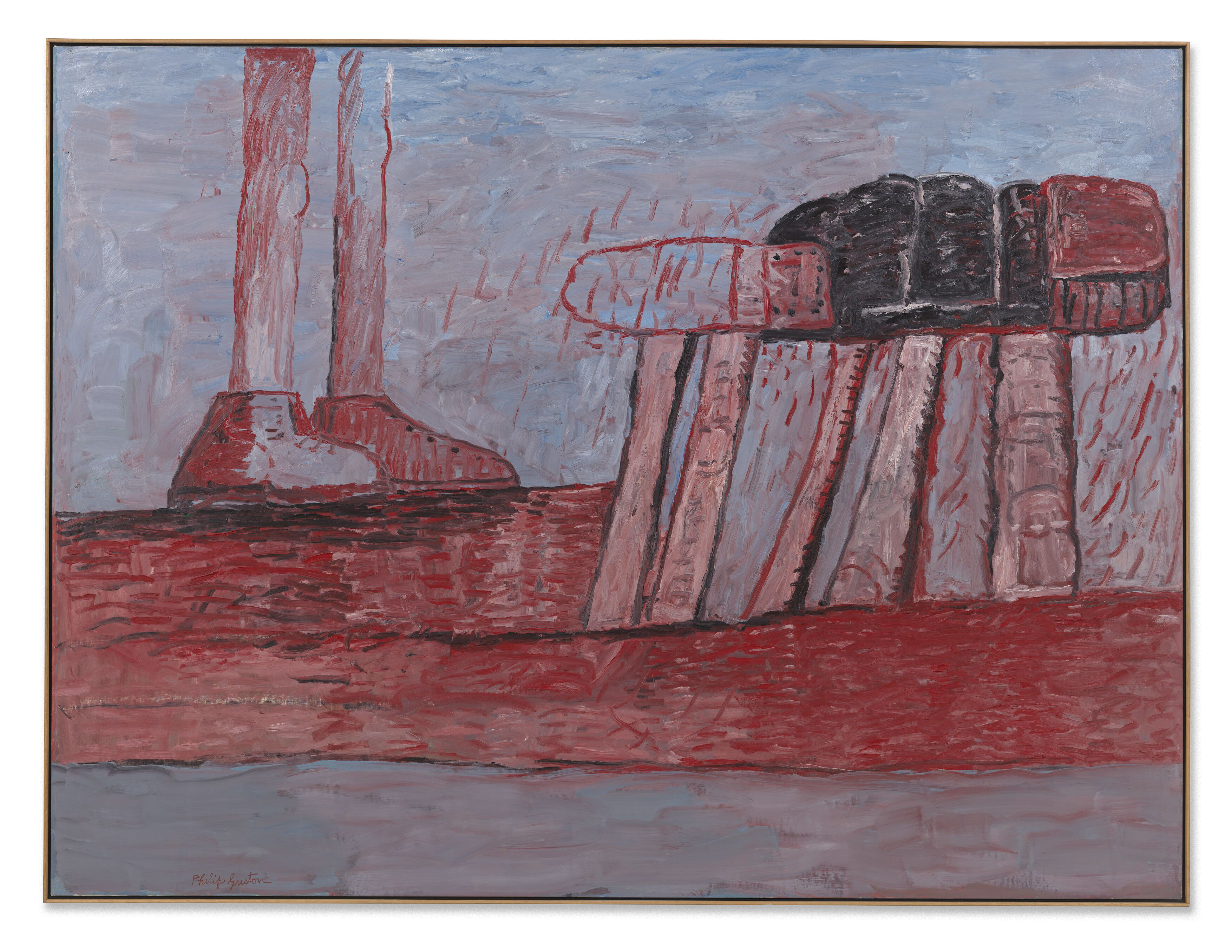

Philip Guston

Lower Level

Lower Level

1975

Oil on canvas

188 x 250.2 cm / 74 x 98 ½ in

191.8 x 254 x 5.3 cm / 75 1/2 x 100 x 2 ⅛ in (framed)

About the artist

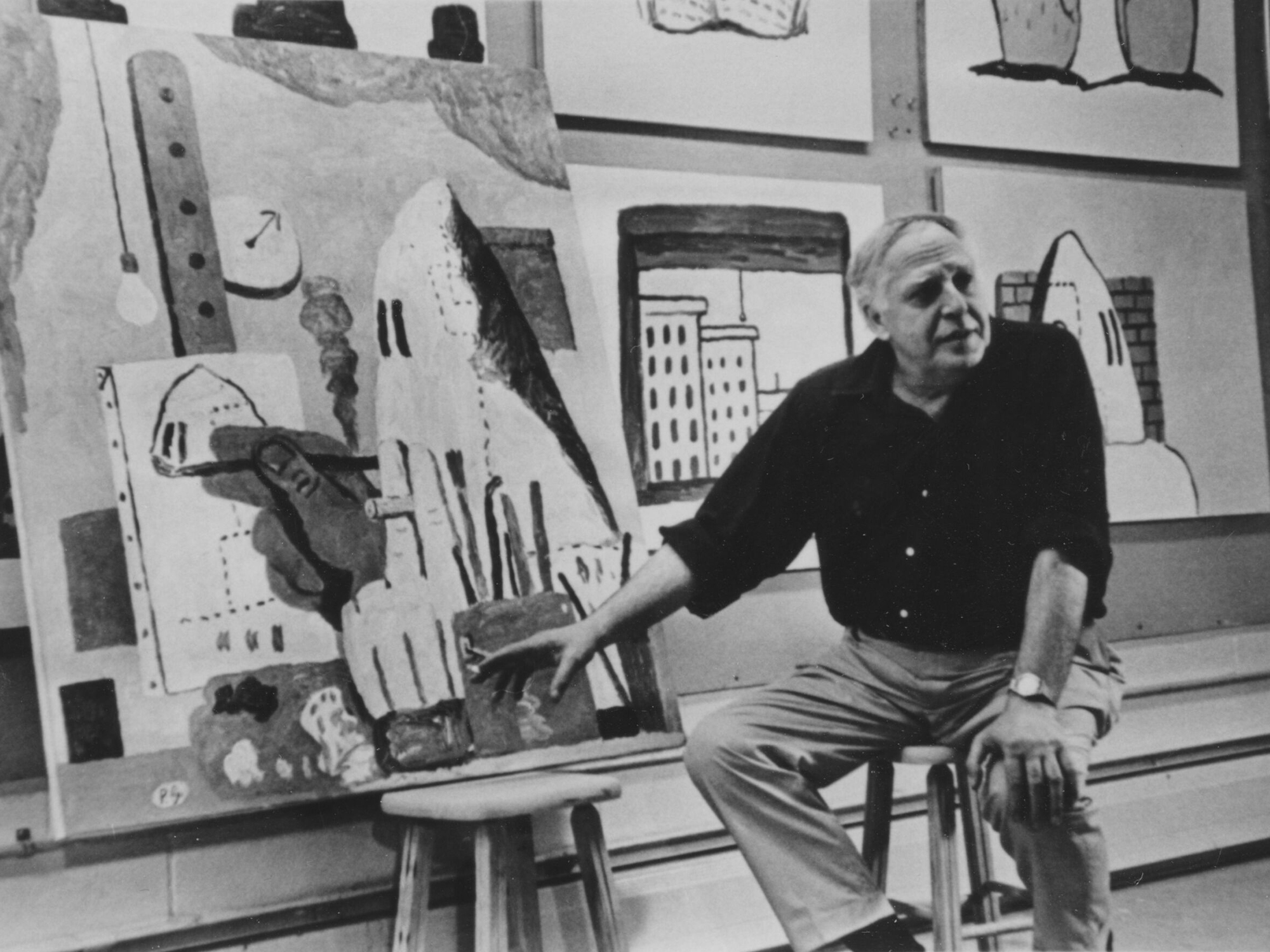

Born in Montreal, Canada in 1913, Philip Guston moved with his family to California in 1919. Except for briefly attending the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1930, he was completely self-taught and went on to become one of the great luminaries of 20th-century art. From his early ties to social realism, the muralist movement, and abstract expressionism to the highly personal and allegorical expressions of his late figurative work, Guston’s commitment to producing art from genuine emotion and lived experience ensures its enduring impact. With a legendary career spanning a half century, Guston’s inimitable oeuvre continues to exert a powerful influence on younger generations of painters.

Born in Montreal, Canada in 1913, Philip Guston moved with his family to California in 1919. Except for briefly attending the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1930, he was completely self-taught and went on to become one of the great luminaries of 20th-century art. From his early ties to social realism, the muralist movement, and abstract expressionism to the highly personal and allegorical expressions of his late figurative work, Guston’s commitment to producing art from genuine emotion and lived experience ensures its enduring impact. With a legendary career spanning a half century, Guston’s inimitable oeuvre continues to exert a powerful influence on younger generations of painters.

Artwork images © The Estate of Philip Guston. Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Portrait of Philip Guston © The Estate of Philip Guston. Photo: Frank Lloyd

1.) Christopher Bucklow, ‘What is in the Dwat: The Universe of Guston’s Final Decade.’ Grasmere/UK: Wordsworth Trust, 2007, p. 88.

2.) Musa Mayer, ‘Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston.’ Zurich/CH: Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2023, p. 307.

3.) Philip Guston, quoted in Andrew Graham-Dixon, ‘A Maker of Worlds: The Later Paintings of Philip Guston’ in Dore Ashton, Michael Auping, Bill Berkson (et al.), ‘Philip Guston. Retrospective,’ London/UK: Thames & Hudson and the Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, p. 58.

4.) Mayer, ‘Night Studio,’ p. 246.

5.) Ibid., p. 248.

6.) Andrew Graham-Dixon, ‘A Maker of Worlds,’ ip. 58.